Documenting the Dance of Survival: Joe Hill on Match in a Haystack

Photo Credit: Dangerous Company

From community theater in childhood to shooting a documentary in a war zone, Joe Hill’s journey as a filmmaker has taken him across continents, formats, and emotional terrain. With a background that spans investigative journalism, global travel, and a deep belief in the power of story, Hill brings a unique lens to his latest project—Match in a Haystack, a daring and intimate portrait of dancers creating art amid the chaos of war. What led him to Ukraine? Why use dance as a language in documentary filmmaking? And how did Misty Copeland get involved? Read on to find out more.

Where are you based?

I just recently moved to Los Angeles and I’m settling into the West Coast. I lived in Brooklyn for nine years before this, and I’m originally from Colorado. I spent a few years after college living abroad and that took me to Qatar, Chile and India.

What inspired you to get into filmmaking?

I was homeschooled, and no one ever taught me how to read when I was younger. But I did go to a community theater at that time to act in plays. Looking back it makes sense that I was telling stories before I could even read. I never felt pulled to one specific format, whether it was theater, film, documentary, audio, I really just cared about the story that we were making and the format that best served what we were trying to say. In college, I was feeling pulled toward telling stories that felt urgent and present. I wanted to feel like I was engaging with the world around me instead of trying to make art as an escape from it. I think that urge is what led me to documentary.

You shot your documentary, Match in a Haystack, in an active warzone. What were the biggest challenges, logistically or emotionally, working under those conditions?

We faced many tough logistical challenges trying to work in Ukraine. Just getting to Kyiv is tricky now because the whole country has been made a no-fly zone. We would have to fly into Poland and then either drive or take a train to Kyiv by land. Curfew was in effect while we were filming, so that meant that we would have to wrap and head back home by 11pm each night. And sometimes during the night we would be woken by the sound of explosions, sirens or anti-air munitions. We were fortunate though that we were supported by so many kind people in the country. The New York Times bureau loaned us a car to use to help us with production while we were there. Our producer, Stefanie Noll, was able to host us in her apartment. I think overall, the generosity we experienced far outweighed the hurdles.

Photo Credit: Dangerous Company

What inspired you to document dancers in Ukraine during this time?

I think I had lost a sense of meaning in the work I was doing as a journalist. I had been producing films for VICE News for the past 5 or 6 years and I had filmed so much pain and suffering around the world. I believe that journalists are supposed to create a historical record of how it feels to be alive during these important moments, but I felt like I had basically only ever created records of death and destruction. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was being covered the same way as usual. I know how urgent it is to document atrocities, but I couldn’t help but think that there was more to history than destruction. There is also life, perseverance, people fighting to cling to their sense of purpose and meaning. I wanted to make a film that was the definitive historical record of the act of creation instead of destruction during a war. That crazy idea led us to search for art in Ukraine and ultimately we found this incredibly inspiring dance group.

How did you prepare to enter Ukraine? Were there specific safety protocols you had to follow?

We had so many security calls before our trip, and we were lucky to still be supported by an expert security team, working for VICE News at the time. Our production was less logistically complicated than many. Kyiv was relatively safe compared to the far east of the country. The most difficult aspect was getting insurance for the team. There is special war zone insurance that was required for our production, but the price is astronomical. This was a major obstacle for us to be able to make this film, especially because most of production was done entirely independently.

What did a typical filming day look like inside a war zone? Were there moments you had to stop filming due to air raid sirens or frontline risks?

I wish there was some kind of typical filming day in Ukraine, but it’s impossible to predict what a day may look like when the war so often derailed your plans. I think that this go with the flow mentality has been created because people generally know that life is not guaranteed. It was only really feasible to plan a day or two in advance. We would hope to go to rehearsals when they were scheduled. We spent a lot of time with the women in the film, even when we weren’t filming because we valued our time together. During the course of filming, we did end up deciding to travel to the frontlines in the far East of the country for one important scene, but for that, you’ll have to watch the film to find out what happened.

Can you talk about the scale of your crew and the gear you used? How did being nimble affect your ability to capture intimacy and authenticity?

Our crew changed dramatically during the course of filming. On our first trip to Ukraine, we were still being supported by VICE News. We had four foreign teammates, two cameras, a director, a producer, and our local teammates, local producer and driver. So in total we were six. It was nice to be able to properly give focus to directing and we were moving around in a big van basically to have enough space. On our second trip, VICE had already gone bankrupt. We had to make the film independently from there. Just Nate Brown, the director of photography, and I went to Ukraine on the second trip. We drove ourselves around, and worked with an incredible local producer Daria Mitiuk. Nate and I each had a Canon c500mkii camera and we shot in vintage Canon FD lenses which had been rehoused in a cinema body. We filmed handheld for everything in the movie except for sitting interviews, and we wore easy-rigs to smooth out our operating. We pulled our own focus of course. I think that the smaller crew size, and directing from behind the camera ultimately worked in our favor. We were able to really keep control of the production itself and we were able to enter moments that felt profoundly intimate and personal because it was really just one of us and one of the participants of the film sitting together in a room.

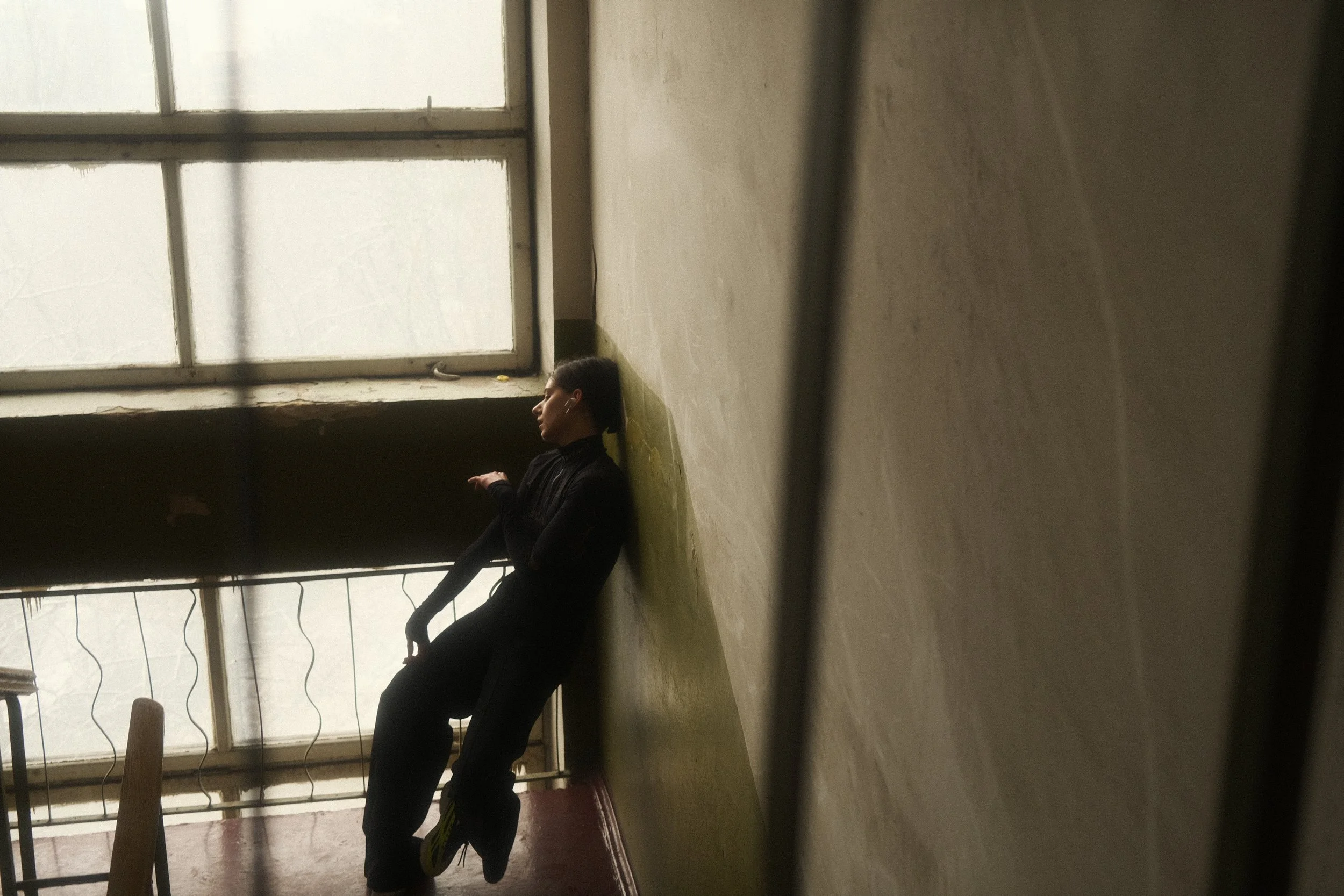

Photo Credit: Dangerous Company

In a war zone, how do you keep creative focus while staying constantly aware of danger?

I think it would be disingenuous to say that we felt constantly under threat during the time that we were in Ukraine. I’d say that oftentimes we settled into the very cool and creative life of Ukrainian artists and then occasionally the war would show its ugly head and remind us where we were.

Did the setting ever influence your directorial decisions, like choosing to shoot a certain way because of curfews or limited access to power or light?

Definitely the curfew was a significant factor for us to manage. We would be out late filming basically every night and then we did have to take into account our filming schedule so that the people we were filming would definitely be able to make it home before curfew. On one occasion, we stayed out too long and the driver we worked with ended up stuck at a checkpoint after curfew until the middle of the night. It was a bad position to put him in and we made sure to never repeat that mistake. Generally, light cuts would be a problem, but also it was part of the story, so we never were too concerned with trying to fight the reality of the situation with our lighting. We shot in very fast lenses so sometimes it felt like we could see in the dark.

Were there moments when you had to put the camera down and just be present with your subjects, perhaps as a human before a filmmaker?

There is definitely a balance when filming intimate or challenging moments that someone may be going through. I think generally the participants of this film trusted us enough to know that we had the best intentions even when we were filming really emotional moments. Sometimes it felt like we knew each other well enough that even in a moment of crisis, when one of them would sneak away to be alone, they were somehow completely alone despite me standing there filming. One particular moment in the film, Yuliia (the performance’s director) sat in the dressing room of the theater alone and cried. I stayed with her filming and I felt in the moment that we were in that room alone together. To me it is one of the most powerful moments of the film and I think that it was just so natural for me to be filming by that point that it didn’t matter whether I was there or not to her. However, we spent so many hours together not filming too. I feel like we struck a balance of how much we filmed. We shared many meals together, carpooled, texted, and spent our days hanging out with the people in the film. For that reason, I think that they trusted us to choose to film moments that we needed to capture and that we wouldn’t force every moment to be part of the story.

The film uses dance almost like an interview language. How did you conceive incorporating choreography into the documentary’s narrative?

I knew that the participants of this film are all dancers, so they are accustomed to expressing themselves through movement. It seems unfair for us to ask them to use only words to describe the way that they feel at this time. We decided to try something we had never done as documentary filmmakers. We would use dance as a form of interview. We chose locations that were significant to each person and then we used the themes and conversations we had already had to shape the questions and prompts we gave them to interpret through movement. The dance sequences were improvised and to me, they serve the film as a window into the subconscious of each person.

Was there a particular moment during filming where you realized dance could communicate something more powerfully than words ever could?

The first time we tried using dance as a form of interview it was clear we had just witnessed something extremely potent. To me it felt like we tapped into something deeply raw. Movement is a universal language. Our theory paid off and when you watch the film in theaters, there are these moments where a standard war documentary suddenly transcends and it feels as though the film has been elevated into some kind of profound and intimate dance film. It was definitely the most experimental aspect of the film and I feel very certain that it paid off.

How did you build trust with the dancers, given the trauma they were processing and the stakes of telling their story authentically?

This process took time. We had to earn their trust and we had to invest deeply in our relationships with each one of them. I would say that our relationships evolved over the course of the year that we were filming. We shared meals off camera, and we shared with them the parts of ourselves that were hidden too, so that it wasn’t just a one way street, inviting them to be vulnerable with no reciprocity.

Did you ever choreograph with the dancers specifically for the camera? Or were you documenting their own creations as they processed trauma and resistance?

We didn’t choreograph any of the movements featured in the film, it was all created by the dancers themselves, and improvised in that moment. Stefanie Noll was our movement director, so she was able to give guidance and prompts that helped them feel supported as they explored this emotional movement, but everything is still rooted in their own form of expression. I do believe this counts as a form of documentary even in these scenes.

Ukraine has a rich history in dance. What made you decide to focus on the dance forms that you did?

It is a very common misconception that this film is about Ukrainian Ballet. The reality is that most of the dancers in this film are strongly opposed to Ballet because to them it feels like a Russian art form. They are exploring a new kind of movement. Some call it contemporary, but really I think Ukrainians are exploring a profound new sense of freedom in their art that they never had experienced under the Soviet Union and under Russian loyalist governments they had before. It felt like the art scene in Ukraine is following in the post-Soviet footsteps of Berlin. Russia’s full-scale invasion threatened that freedom across all forms, but dance to our team felt like the most evocative and visual way to convey that inner sense of freedom we wanted to bring to the screen.

Speaking of dancing, how did Misty Copeland come on board as executive producer? Did she reach out to you, or did you pitch it to her?

I actually just emailed her team. I shared information about the film and the values that were driving our team. Misty and her producing partner, Leyla Fayyaz, just responded to the film viscerally and agreed to help use their platform to uplift the film as much as they could.

What does it mean for the project, symbolically and practically, to have one of the most iconic dancers in the world championing Ukrainian artists?

Tangibly, I hope that it gives the film some sense of credibility and invites an enormous audience of dancers who maybe otherwise wouldn’t be focused on what’s taking place in Ukraine to come and experience this film. On a more personal level, I think the women featured in the film were deeply moved to know that their stories struck a chord and were garnering the attention of someone they also were deeply inspired by.

You’ve worked with VICE before, but this feels more cinematic than traditional VICE documentaries. How did your partnerships evolve for Match in a Haystack?

This film began as a VICE production when I was still working there as a staff producer. However, the timing of our project landed right at the same time that VICE was downsizing and when they declared bankruptcy. Unfortunately, that meant that we no longer had a real studio partner, we had to finish the film independently. I would say that even when it was a part of the VICE ecosystem, they knew that this was something unique and different from their usual approach, and while that required a large amount of lobbying to get it approved, I think that was what ultimately excited them about the idea.

VICE is known for gritty journalism. How did you balance their reporting ethos with the emotional and artistic tone of this film?

I was fortunate enough to be given a huge amount of independence in making this film even when it was still under the VICE umbrella. This is my directorial debut as a feature film, and I was lucky that both under VICE and with the partners who joined the team to support this as an independent project, everyone seemed to really grant our whole team the space to make creative decisions and push for this to be something that I feel is unique and unlike any other war coverage I’ve seen to this point.

Your new studio, Dangerous Company, was featured in Variety right as Match in a Haystack was coming together. How does this film reflect the kind of content you aim to produce through your studio?

Dangerous Company was built on a set of principles. We believe that stories are a human’s fundamental tool to navigate an incomprehensible world. Since the world is basically impossible to even wrap our heads around, storytellers sit and wrestle and try to find some form of looking at things that provides an audience with some semblance of meaning in all of this. We plan to continue to create films that give us an outlet to navigate things around us and we hope that experience is also meaningful and appreciated by our audiences.

Your earlier work, whether horror fiction, comics, or investigative journalism, emphasizes suspense and emotional engagement. How did that translate to your nonfiction work in Match in a Haystack?

I think the vast majority of my non-fiction work is still inspired by what I’ve learned about the fundamentals of story. I believe that stories are best told with compelling characters at the center. I think stories have to have a character who has a strong desire or goal, obstacles in their way, and a willingness to try to overcome those obstacles. This is true in all kinds of stories, but in documentary, you have to really search to find these components.

Photo Credit: Dangerous Company

What does it mean to you to premiere at NYC’s Angelika Theater alongside Misty Copeland in the Q&A?

Premiering at the Angelika Theater in the Ukrainian Village of New York City felt like the exact right place to do it. I was overcome by the generous support of my friends, family and so many other people who came out for the premiere. I will admit that no matter how important it felt to me to premiere the film in NYC, I’m more excited, and I think more nervous to premiere the film in Ukraine this year at the Odessa Film Festival.

What is one key insight about resilience, storytelling, collaboration, or the Ukrainian spirit that this experience taught you both personally and professionally?

This experience just reminded me that we have very little control over the world at all. It’s overwhelming and honestly most of the time pretty terrible. But sometimes we do get to control the way we spend our own time and the people we spend it with. I believe it’s ok for us to let ourselves feel joy despite the world being horrible. I think we can still hold on to our purpose and the things that make us who we are for as long as we can.

What would you like to see for the future of Ukrainian dancers?

Not every dancer in Ukraine is fortunate enough to be able to make the choice to continue dancing. So many others have fled the country, or have gone to the frontlines to fight. I hope for a future where people do not have to fight to be able to stay true to who they are and to spend their time doing things that bring their lives meaning.

What is your motto in life?

Make the thing that’s what you need to say, not what you want to talk about.

To learn more about Joe Hill and his projects, visit the links below:

Tickets + Screening dates, Personal Instagram, Company Instagram, Tik Tok